Richards Center director Rachel Shelden recently published an article in the Journal of American Constitutional History. In the words of legal historian Julian Davis Mortenson, it’s “a big deal.”

Shelden argues through an analysis of the Civil War era Congressional Globe that 19th-century Congress reflected public thought and thus uses the Globe to understand what the 14th Amendment meant to the American public. Read here.

Abstract:

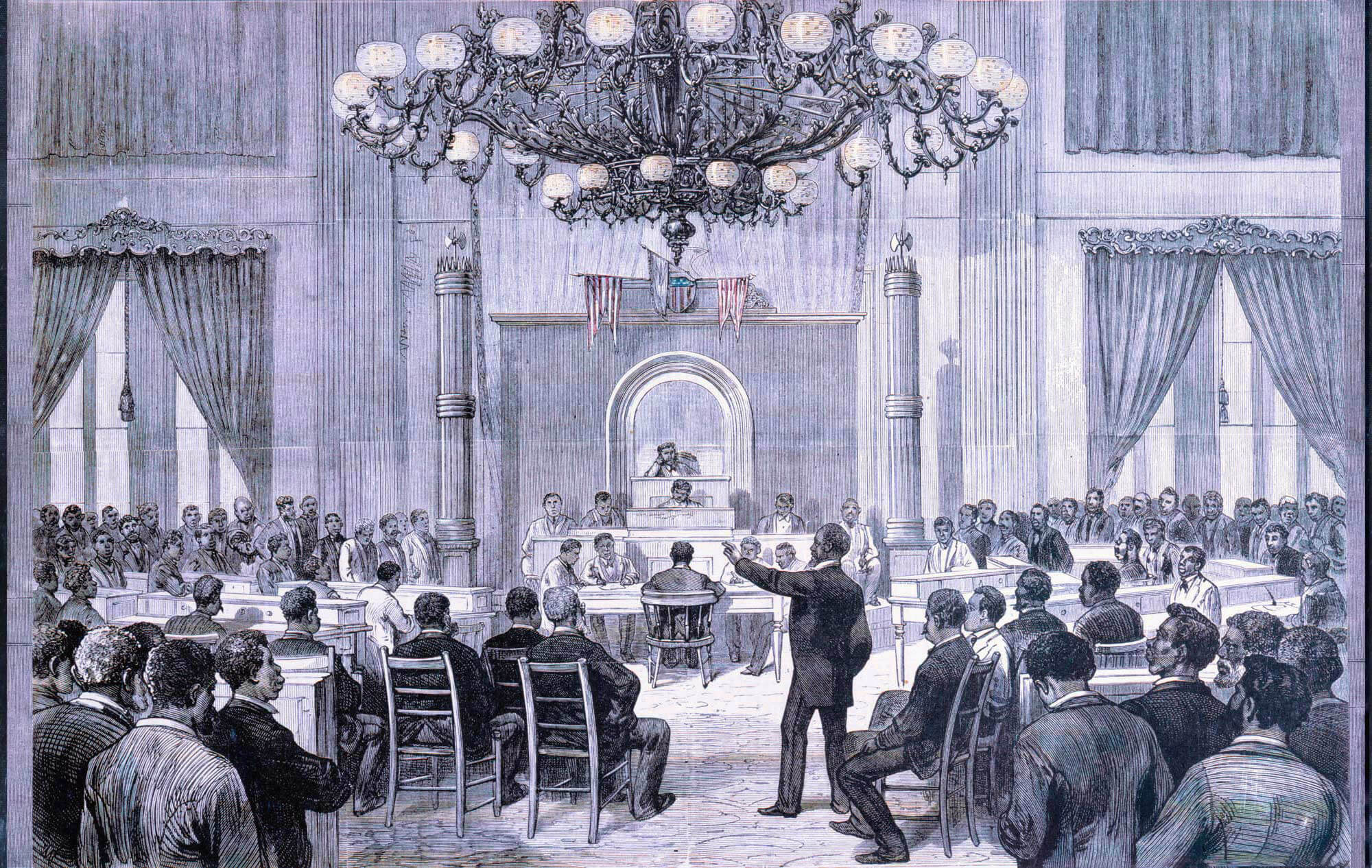

Few legislative terms left a bigger mark on U.S. constitutional law than the first session of the Thirty-Ninth Congress, which met from December 1865 through July 1866. Although legislative history has become more controversial in modern legal interpretation amid the rise of public meaning originalism, this session and the men who drafted the Fourteenth Amendment so fundamentally altered the constitutional politics of modern America that their stories remain the subject of deep scholarly interest and fierce debate. In Punish Treason, Reward Loyalty, Mark Graber takes a comprehensive look at this session through the Congressional Globe—which then served as the “official” records of the legislative branch—to explain the broader constitutional and political considerations of the men who framed the Fourteenth Amendment. Using the Globe’s text, Graber argues that Sections 2, 3, and 4 were the heart of that amendment, rather than the better-known Section 1. Yet, a closer look at the context in which the Congressional Globe operated shows that such debates were far from an accurate depiction of congressional business. Instead, the Globe’s pages contained an outsized number of “buncombe” speeches designed for constituents rather than for persuading or negotiating with colleagues; the men who make up Graber’s book used these speeches as a tool of dialogue with the broader public. Ultimately, the Globe may tell us just as much about the public meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment—and many other constitutional and statutory concerns—as it does about legislative intent.